Have you ever noticed how quickly your blood sugar climbs in the morning? Is your morning glucose reading occasionally the highest of the day? If this is the case, you are not alone.

Increasingly, people are experiencing the “dawn effect” or “dawn phenomenon” as low-carb diets and intermittent fasting become increasingly popular. But what causes it? And, more significantly, is it cause for concern?

This tutorial will take you through the science of the dawn effect, concentrating on what we know and don’t know as it relates to a low-carb diet.

What is the dawn effect?

The dawn effect is an unexpected rise in fasting blood sugar shortly after awakening. It was discovered in individuals with type 1 diabetes in the 1980s. The dawn effect was characterized as rising blood sugar levels without the typical compensating rise in insulin. (1)

The body typically boosts glucose synthesis as dawn approaches. However, the insulin the patients had taken the night before was inadequate to limit the glucose rise. The mismatch increased blood glucose levels.

Researchers discovered that a spike in the “counterregulatory hormones” cortisol, adrenaline, and norepinephrine triggered the early morning glucose rise. (2) They are known as counterregulatory hormones because they “counteract” the actions of insulin.

These anti-insulin hormones induce the liver to produce glucose in the body. When an individual has a typical insulin response, their insulin level rises to maintain a stable blood glucose level.

Extra glucose circulates until it is taken up by cells and utilized for energy in people experiencing the dawn effect. Consider this the body preparing for the more significant energy needs required to get u,p and ensuring that adequate glucose is available for utilization when a person becomes active each morning.

According to studies in adults who do not have diabetes, the body boosts insulin production between 4 and 8 a.m. This additional insulin spike regulates the increased blood glucose levels caused by the counterregulatory hormones. (3)

As a result, for decades, it was considered that the dawn effect primarily affected those with type 1 or type 2 diabetes. That presumption, though, may be changing.

Implications

A pronounced dawn effect in patients with diabetes indicates an inability to regulate morning blood sugar, which may have long-term health effects.

According to one study, the dawn effect is related to a 0.4% (4 mmol/mol) increase in HbA1c values, representing the 3-month average of blood sugar levels. (4)

Because greater HbA1c levels are associated with a higher risk of problems, the dawn effect is expected to affect people with diabetes negatively. The current suggestion is to aggressively address the dawn effect with drugs to enhance overall glucose management. (5)

What about those who do not have diabetes? What if they eat a low-carb diet and preferentially burn fat for fuel rather than glucose? Would the dawning impact have the same consequences? That’s what we’ll look into next.

The dawn effect in fat burners

The negative news comes first. We are unaware of any scientific research investigating the dawn effect in people on a low-carb diet.

However, based on clinical experience, the morning effect is typical among people following a rigorous low-carb diet.

Keep in mind the physiology. As you approach closer to waking up, your body secretes counterregulatory hormones that boost the liver’s glucose production. However, if blood glucose levels rise, the compensatory surge in insulin is absent. Why would this be the case?

Again, there is no complex data to explain why blood sugar levels rise, although suggestions exist.

According to one explanation, the pancreas does not need to respond quickly to increased blood sugar since it seldom occurs on a very low-carb diet. The feedback loop rebalances. (6)

Another notion is centered on muscle cells. Muscle cells are the primary engine of glucose absorption under glucose-burning circumstances, sucking glucose from the blood for energy use.

However, when your cells predominantly burn fat for fuel, as when you drastically limit your carbohydrate intake, your muscle cells don’t require glucose. The brain, on the other hand, continues to require glucose. Muscle cells become “glucose resistant,” allowing the brain to be “first in line” for available glucose.

This physiological mechanism is “adaptive glucose sparing” or “physiologic insulin resistance.” The premise is that a lack of glucose absorption occurs for a good purpose rather than a negative one, as it does in diabetes. Again, this is a theory, but it makes sense regarding how the body functions.

Some argue that insulin resistance gave our hunter-gatherer ancestors an evolutionary edge by allowing their brains to utilize glucose while encouraging their muscles to run on fat. (7)

The presence or absence of high insulin levels may represent a critical distinction between potentially hazardous and presumably benign elevated glucose levels. Raised glucose in an insulin-resistant condition with increased insulin levels is likely to have a different biological effect than the same glucose in an insulin-sensitive setting with low insulin levels.

While this does not guarantee that the two conditions will result in different results, the differences in the body imply that they may.

Is the dawn effect always harmful?

While evidence shows that the dawn effect may be hazardous to those with type 2 diabetes, can we say the same for those who do not have diabetes? (8)

With research to help us, we can rely on our best reasoning abilities to arrive at a theory.

Blood glucose is detrimental in two ways. The first is when blood glucose levels are chronically raised, and the second is when there are substantial rises or “spikes,” which is known as glucose variability.

According to research, these pathways accelerate vascular and endothelial dysfunction. (9)

We may conclude that there should be no vascular or other health repercussions if none of these issues exist — no persistent elevation, and the rise or spike is minor.

How can we describe or quantify “chronic elevation?” HbA1c is commonly used to assess it. The greater the difference, the higher the average blood sugar. It’s not perfect, but it’s a valuable sign of persistent blood sugar increase.

HbA1c, on the other hand, may not account for shorter, more extreme blood sugar spikes, commonly known as glycemic variability.

It is typical for post-meal glucose levels to rise to 140 mg/dL (7.8 mmol/L). (10)

As a result, a morning impact of up to 140 mg/dL (7.8 mmol/L) is not caused by the alarm.

This is especially true if morning blood sugar levels are the highest of the day and post-meal levels are much lower after low-carb meals. Again, there is no data to support this. Thus, it is only a supposition. However, it makes sense.

According to this idea, if HbA1c is normal or improving, dawn blood glucose levels do not exceed 140 mg/dL (7.8mmol/L), and post-meal rises are less than 140 mg/dL (7.8mmol/L), the dawn effect is not a therapeutic issue.

If these requirements are not satisfied, the morning elevation may exacerbate an existing issue and hasten vascular damage.

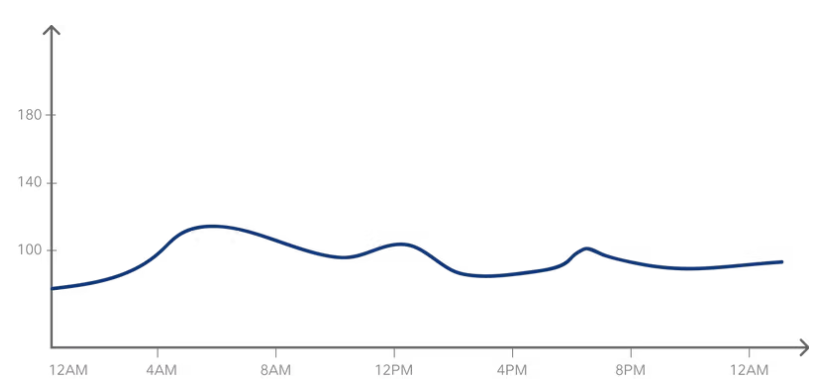

As an illustration, below is a continuous glucose monitor (CGM) graph that indicates a higher likelihood that the dawn effect would not have significant health repercussions. The peak glucose level is 120 mg/dL (6.7 mmol/L), the highest of the day, with post-meal peaks remaining below 110 mg/dL (6.1 mmol/L) and reverting to baseline within an hour.

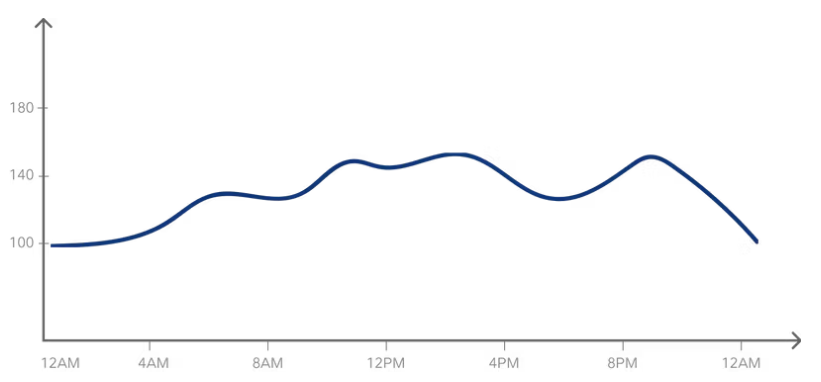

Conversely, this graph implies that the dawning impact is part of a broader issue. Blood sugar levels begin high, with a peak of 130 mg/dL (7.2 mmol/L), and never return to baseline before climbing to well beyond 140 mg/dL (7.8 mmol/L) following meals.

The following are the differences between these two graphs:

- The extent to which blood sugar levels have risen

- The duration of the blood sugar increase

- The most likely underlying mechanisms for blood sugar elevation

Can you decrease the dawn effect?

The dawn effect may not be an issue for certain people. But if you believe it may harm your health, what can you do to mitigate it?

- Exercise may be beneficial. Physical activity after supper and first thing in the morning may lessen the extent and duration of the glucose spike.

- Eating first thing in the morning can also help decrease the dawn effect. This advice may need to be revised. Isn’t eating bad for your blood sugar? Not in this instance.

Remember that the dawn effect is generated by lower-than-normal insulin production in the morning to guarantee optimal glucose levels. If you consume anything, your body will get a signal that you have enough energy, and your insulin may respond correctly. Consequently, you have enough insulin to assist in lowering your glucose level.

- Some individuals advocate having a low-carb, high-fat, or high-protein snack before bedtime to reduce the morning effect. This is not a good solution for people who want to profit from intermittent fasting. However, it may be a better option than taking medicine. Each individual should decide whether or not this proposal is appropriate for them.

- If you test your blood glucose in the morning, you’ll be able to know if this method is effective.

- Pay attention to the significance of sleep! A lack of sleep can enhance cortisol production, resulting in a more pronounced morning impact. (11)

- Finally, some people may consider using drugs. In the evening, insulin is more effective than oral diabetes drugs at lowering the degree and duration of glucose increase. (12)

All drugs, particularly insulin, have possible adverse effects, including the possibility of dangerously low blood sugar. You should discuss prospective drug modifications with your doctor and request a complete risk-benefit analysis.

The Bottom Line

We know a lot about the dawn effect and how it links to diabetes and an increased risk of complications. We know substantially less about the dawn effect in persons who follow a low-carb diet and whose muscles predominantly burn fat for fuel rather than glucose.

The slight morning blood sugar spike is most likely an adaptation that is not harmful. However, until additional scientific data is available, it is good to discuss morning blood sugar increases with a healthcare provider and, if they are problematic, evaluate available strategies to manage them.

0 Comments